Antarctica bound

Pat and Rosemarie Keough went to the end of the Earth to create 'the most perfect book in the world.' The result: a $4,500 wonder of nature

Bruce Ward

The Ottawa Citizen

Sunday, March 02, 2003

Pat Keough is kidding when he tells you to bend your knees when lifting Antarctica, the weighty photography art book he created with his wife, Rosemarie.

What he doesn't tell you is that the 12.5-kilogram book will bend your mind, starting with its $4,500 price tag.

"It feels nice, looks nice and even has a nice sound," Rosemarie says down the phone from the couple's home on Salt Spring Island, B.C. "When you drop the covers, there's this real beautiful solid sound. Not too many books can claim to stimulate all the senses."

But then there's no other book like Antarctica.

It was bound in Georgetown, Ont., using methods developed in the High Renaissance, and printed in Burnaby, B.C. with technology that triples the resolution of the usual high-end lithography. The detailing would make Martha Stewart drool: the covers are morocco, a high quality goat leather, chosen so as to last centuries. The paper, with satin enamel finish, is from Wisconsin, the thread is Irish and the endpapers are made of grey flocked velvet from France. The book arrives in a linen and velvet presentation case — the book alone weighs 8.6 kilograms — and all but a few of its 336 pages display colour photos.

Only 1,000 copies will be produced and, so far, buyers include Robert Bateman, and travel clothing manufacturer Alex Tilley. Antarctica already graces the libraries of such pedigreed nature-lovers as Queen Noor of Jordan, Prince Bernhard of the Netherlands, the Grand Duke of Luxembourg and the Prince of Wales.

"The book weighs 19 pounds, yet you can take it by the covers and shake it like a piece of laundry and it won't fall apart," says Pat, 57. "The package is a piece of art and the people buying it are looking for something exclusive. We want our books to last hundreds of years."

But why bother? A book, even an enterprising and exquisite one like Antarctica, seems like an anachronism in the CD-ROM era.

"That's like asking a sculptor, 'Why do you bother to sculpt in granite because you could just look at your design in Auto CAD on the computer,'" says Rosemarie, 43. "Yeah, you could see it but you don't have the full three-dimensional tactile intellectual stimulation, and to us a book has this appeal."

Adds Pat: "So much of what we produce is here today and gone tomorrow. In the fast world we live in, there is a certain nostalgia for perceived good old things. A beautiful book, something that is a classic, has that appeal to people. It's something you can put your hands on. You put your hand on a disc, a CD, it's just a round piece of plastic."

British artist David Hockney has said that photography is the child of painting. The Keoughs' book is evidence that this is so. Some photos of explorers' graves and abandoned whaling stations seem almost too real, like the paintings of Alex Colville.

The subtle colourings evident in the photos are perhaps the biggest surprise to those who think Antarctica is merely ice, snow and rock.

"You see images where an entire ice cap is watermelon pink, and the next ice cap is lime green," says Rosemarie. "This is because the most common organism in Antarctica is the snow algae, a microscopic organism that lives on the first couple of inches of the snow. The snow starts to rot as summer months progress, and the surface becomes more of an aqueous environment. It combines with bits of phosphates that are blown up on sea spray and you get a bloom of algae. One week you will see whole areas that are splashes of colour. The next week it's back to normal: pure white."

The Keoughs were also captivated by the shifting shades of light.

"Antarctica is a desert, very arid, so you have extreme clarity in the air," Rosemarie explains. "Depending on when you are there — what month and at what latitude — you have lingering twilight. The sun doesn't set for six months, it gets lower in the sky and you will have this beautiful pink light or golden-coloured light that lingers for hours and hours.

"We had a most memorable experience in Crystal Sound. As evening came on, there were bergy bits, growlers and icebergs — these are actual scientific terms for different sizes of icebergs. In the background there were cliffs of ice and snow-capped peaks. The colours went from a peachy colour with streaks of apricot while these icebergs were royal blue. It progressed until the water was a deep burgundy color and the ice went to navy blue. It kept changing until the water became more golden again. It keep changing, minute after minute. You pinch yourself, and say 'I'm seeing the most remarkable display of colour of my whole life.' Then a half hour later, you say 'now I'm seeing the most spectacular natural event.' It just keep progressing in the most remarkable way."

The Keoughs' first book was a self-published photo essay on the Ottawa Valley, which sold 20,000 copies in 1986. (Long-time Citizen readers may remember their travel pieces for the paper in the 1980s when the couple lived in Renfrew.)

In 1988, they produced a book on the Nahanni River in the Northwest Territories. It was published by Stoddard and sold 20,000 copies. A 1990 book on the Niagara Escarpment, also published by Stoddard, sold another 27,000 copies.

Antarctica is self-financed and net proceeds from the book — $700 from each $4,500 sale — will be given to BirdLife International's Save the Albatross fund.

"Our form of philanthropy is to invest money in something we know — photography and books — to create a product that can be sold to help albatrosses, which are being wiped out by long-line fishing," says Pat.

Rosemarie says they accepted the risks involved in the project, which was carried out over two austral summers — between November and March — in Antarctica. They shot nearly 800 rolls of film.

"We were determined to come back with really fine and unusual images of Emperor penguins, which are the world's most remote bird," she says. "And it's really dicey to get to a rookery, there's not that many. The adults brood their eggs on their feet standing on the sea ice. They're the only bird that doesn't have to come to land to brood its young. You could be waiting and waiting at a base camp for ideal weather conditions to fly by Twin Otter seven to 10 hours to a penguin colony and two or three weeks might slip by before you got clear enough weather. And by then the ice is broken up, the colony has disintegrated and young have perished because they don't have their adult plumage yet and there's no penguins to photograph. I have met people who have tried three or four years in a row to spend time amongst the Emperors and weren't successful."

Usually, the Keoughs work together but they split up to photograph the penguins. Rosemarie went to an area of the continent lying south of Africa; Pat went to a region south of Australia and New Zealand.

"We went to two different parts to be sure we had the best chance possible and sure enough we both came back with wonderful images," says Rosemarie. "While I was camped out with the Emperors for several weeks there was a severe blizzard. This is exactly one of the things we wanted to photograph — it can't be all clear blue skies. We wanted variety and to show what this habitat is like. So you kind of swallow, and say 'All right, I'm gonna head out in the blizzard,'" she laughs.

"The number of pictures you can take is quite finite. You can't change film, can't even change lenses. The snow is blowing, blowing, blowing. So I had three camera bodies around my neck and three lenses and three rolls of film to shoot and that was it.

"From our camp — just a couple of tents and a Twin Otter aircraft at the edge of Dawson-Lambton glacier on the coast of the Weddell Sea — we had a bamboo pole line with red flags every 50 feet to where the colony had been. Every day the colony moved downwind a couple of hundred feet — the reason being they defecate where they are and they have to eat the snow for water so they keep moving to cleaner snow. So our pole line was no longer at the back — it was a long way away from the rookery.

"So I followed the pole line and and kept going. I came to about 4,000 Emperor penguins and walked to the head of the group. In inclement weather, the penguins form a pyramid shape with the point away from the wind. The birds at the back break the wind for the rest of the colony. When the ones at the back get cold they toboggan on their bellies to the front and eventually they're enveloped. They rotate, some are warm and some are cooling off.

"So I was able to photograph this formation. It was phenomenal. About the time I finished my film the storm got worse.

"I'm walking back to the back end of the colony into the wind and I know that those bamboo poles are a couple hundred yards or metres ahead. But where's ahead? The whole world is white: the sky, the snow, the ice, the glacier, everything is a consistent shade of white. When you walk you do not even know where your foot is going. And I'm thinking, 'Do I just strike for where I think the bamboo pole is?' because if you miss it, it's game over. It was quite something standing beside the last of the penguins, the last warm-blooded creature, and making that decision as to what to do.

The Keoughs' book, weighing 12.5-kilo-grams with its linen and velvet case, is designed to last for centuries.

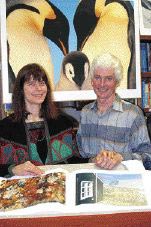

photo;Derrick Lundy, Citizen Special

Emperor penguins -- adults and chick.

Southern elephant seals in annual moult, South Georgia.

In repose, adult Weddell seal.

Gaff-rigged cutter Dagmar Aaem off Point Wild, Elephant Island.

(The book)

Killer whales and tabular iceberg off Ross Ice Shelf.

Weddell seal, female and pup.

Sunrise, Cape Renard, north entrance to Lemarie Channel.

Immature kelp gull patrols the tideline, Galindez Island.

Norwegian whaling-era vessel decaying at Godthul, South Georgia.

Storm, Southern Ocean, wandering albatross.

Emperor penguins in

white-out.

"I thought, 'Well, I'll just stay here a little while. I thought of my husband far way, and said, 'Pat, these are great shots, you gonna love them.' So I waited there to see if the winds would die down somewhat. To be honest, I have no idea how long I was there, it could have been hours. We had an expedition leader with us, and he came out with a rope from the last pole and said 'Rosemarie, it's time to head in, there could be 72 hours of this storm.' You take calculated risks in order to get the shots you're after, to get something really different."

Rosemarie's photo of the penguins' scrum was used as the book's title page.

"It's an environment where the snow and cold are brutal, and you're really insignificant, your presence means nothing. But it's exhilarating," she says. "To be amongst nature, that's a real high the whole time.

"It's just an amazing thing to see so many creatures in their own habitat and they aren't afraid of you because the animals and birds have never been hunted. There are no predators, no indigenous humans, no wolves, no bear, no wolverines, nothing. Their predators come from the ocean — killer whales and leopard seals. You're literally amongst thousands of creatures and they accept you ... it's just the most marvellous experience."

The Keoughs used 35mm cameras and usually carried half a dozen camera bodies on every shoot, including a couple tucked inside their parkas. "If one camera seized up because it got too cold, you'd just bring one out from under the parka and away you'd go," says Pat.

"Because it's a polar desert, the snow is incredibly dry, just like talcum powder at times, and it will infiltrate into any little crack. If it gets inside the camera, you don't want it to melt so you don't dare take it in where it's warm. You have to strip it down in a tent outside at 30 below, strip it down and use a fine brush to clear out the snow."

Rosemarie describes the book as a mix of technology.

"The printing is state-of-the-art computer technology but the binding is a revival of Renaissance binding from 1400-1500. It's very tactile. We've used beautiful materials like leather and velvet. It smells and feels wonderful."

The book has won the Benjamin Franklin Award for production excellence from the Printing Industry of America as well as the first Craft Art Science Award from the International Printing House Craftsman, based in the U.S.

"The book required years of research into how books are put together," says Pat. "We wanted to create the most perfect book in the world. We were willing to go anywhere in the world to bind the book and anywhere to print it to get best quality possibility. We looked in Japan and Italy and New Zealand."

The best turned out to the Felton Bookbindery in Georgetown, Ont. and Hemlock Printers in Burnaby.

"They came through in spades," says Pat. "It became a fully Canadian production. I guess you could say it's an amalgamation of Canadian talent that put this thing together."

Bruce Ward writes for the Citizen's Weekly.