ICE PACT

Drawn up to protect the last great wilderness, the Antarctic Treaty encourages mainly scientific exploration. But for armchair adventurers, a photographic account of the frozen continent may be the next best thing.

Antarctica has attracted adventurers since 1773, when British explorer James Cook became the first person to venture inside the polar circle. The continent itself was discovered in the 1820s, when it was first sighted (separately by Edward Bransfield and von Bellingshausen). Then, between 1901 and 1904, came the extensive exploration by Robert Falcon Scott, followed by his and Ernest Shackleton’s combined and separate attempts to reach the South Pole. But it was Roald Amundsen who got there first – on December 14, 1911 – more than a month before Scott, who then, famously, perished on his return.

Even before those legendary events there were many more tales of exploration. In 1841, Sir James Clark Ross discovered the Ross Sea, Mount Erebus, and the Ross Ice Shelf. (If he’d beaten Amundsen, would we now be talking about the Ross Pole?) In 1898, Adrien de Gerlache, in the Belgica, was trapped in the ice but still managed to win the accolade of first to survive an Antarctic winter. Since then the stories of hardship, courage, tragedy, and triumph have continued, and reading through the list you see a common goal – to be the first, the best, the bravest, to go farther, to try harder, to achieve more. Why? Why does anyone do anything remarkable? For a stab at immortality? To enrich the spirit?

Of course, Antarctica has also been explored for material gain – whales and seals being the treasure. And it’s been used for scientific research purposes – 400,000 years of climate change are recorded in the ice, yielding invaluable data on global warming.

The latest footsteps are those of the tourists; thousands of people per year tramp through the huts built by the earliest explorers. (These relics from the past remain eerily intact as polar conditions ensure that no dust has collected there.) The question now is, should we leave it alone? As each adventurer, scientist, and entrepreneur stakes his or her claim on the continent, do they take a bite out of the ice?

Protecting Antarctica is complicated by the fact that no single authority governs it. Instead, the Antarctic Treaty exists to maintain the last great wilderness and, to date, 45 countries comprising 80 percent of the world’s population have acceded to it. Now, as the world becomes more environmentally enlightened, the accolades are less for winning the race and more for preserving the racetrack.

One such project – a book of photographs – has the awards rolling in. Canadian husband and wife Pat and Rosemarie Keough spent two austral summers on the continent and hung off lurching boats and ice caps to take some truly incredible pictures, which they have published in Antarctica, one of the most beautiful handmade books ever produced, printed in a limited edition of 950 copies. It captures the geography and spirit of the place and also raises funds for one of the Antarctic’s most endangered inhabitants, the albatross.

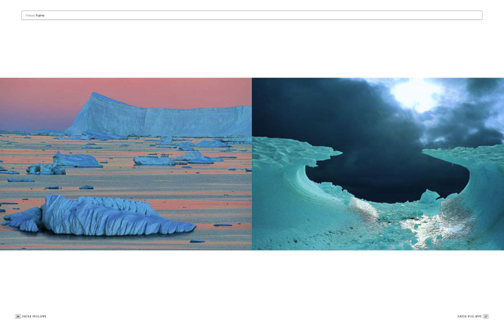

The Keoughs’ photographs are remarkable for their quality but also for their breadth of subject, ranging from wildlife, landscapes, and abstract natural patterns to the monuments of the explorers and the whaling industry. They take us from the windswept polar plateau of the interior to the mountainous coast, and from the off-lying islands to the icy seas and surrounding Southern Ocean. Each page conveys a sense of the vast emptiness of this continent. “In Antarctica, man is insignificant and vulnerable in an all-powerful, awe-inspiring environment,” says Pat. “And that’s part of the attraction,” Rosemarie adds.

The awards from such prestigious institutions as the Royal Geographical Society include World’s Best Photography Book, Nature Photographer of the Year, Outstanding Book of the Year, Craft Art Science Award, and the list goes on – 21 so far, and counting. It’s not just the photography that is impressive, it’s the book itself. This is a huge tome weighing 26.7 pounds, put together using traditional binding techniques and materials sourced from all over the world – leather from Scotland, velvet from France. It will last far longer than any ordinary volume and become not just a book but a covetable work of art – a shrine, even, to the frozen continent and its inhabitants.

However, even this well-intentioned masterpiece raises a question. Will we sit back in our armchairs, content to appreciate Antarctica through the Keoughs’ lens? Or will we feel the need to press our own footsteps into the fresh snow? Is the need to discover and explore new lands in all of us? Lars Lindblad, leader of the first commercial Antarctic cruise in 1966, thought we should encourage this trait, for the sake of conservation if nothing else. “You can’t protect what you don’t know,” he said.

But Sir Peter Scott, founder of the WWF and son of Robert Falcon Scott, disagreed. As he said, “We should have the sense to leave just one place alone.”

PATEK PHILIPPE

|

|

|

|

|

|