Passion for Excellence

Keough Update #17: LABYRINTH SUBLIME

Preparing Chieftain Goat Leather — May 10, 2011

Greetings Everyone

Following are several photos to describe Hewit’s tanning process to make the morocco Chieftain goat leather. We took half these photos years ago when visiting Hewit in Scotland; the other photographic credits belong to Hewit’s Directors Roger Barlee and David Lanning who kindly took these photos during the actual tanning and dressing of the Chieftain Leather for LABYRINTH SUBLIME.

Bales of goat hides arrive at Hewits from India and Bangladesh. These hides are a value-added by-product of the food industry whose prime function is to produce meat for human consumption. The local leather agent pre-selects hides that have a minimum of blemishes. Just one percent of the hides viewed by the agent are considered good enough to forward to Hewit. To preserve the hides during shipment to Scotland, they have been tanned in their country of origin.

Hewit’s Director Roger Barlee, chemist and tanner, inspects the goat hides for blemishes, as Rosemarie looks on. Roger then sorts the hides under natural day-light beneath a north facing skylight and allocates them based upon size and quality for specific orders.

Hewit produces three quality grades of Chieftain, determined by the size and number of blemishes in the hide — a flay mark on the back of the skin, scratches, scars, perhaps even holes in the skin from insect damage. This is a natural product and perfection is rare. Grade I, deemed flawless, commands a 43% premium over Grade II and nearly 400% over Grade III. Of the one percent of hides that are selected for shipment to Hewit, only 10% of these are fine enough to be processed into Grade I Chieftain. Of course, the Chieftain procured to bind our tomes are without exception all Grade I. These hides were hard to source given the large size required for our covers.

Within these metal safety cages revolve huge wooden drums. The processes that follow take place within these drums. First the goat hides are soaked and washed thoroughly to remove the majority of the local (unknown) tannage and anything else that may yet be adhering to the hides. The next step is to stabilize the rehydrated hides and transforming them into a durable, flexible leather. An increasing concentration of vegetable tanning agents (a combination of sumac, tara and myrobalan) are added to the liquor which is allowed to thoroughly penetrate the hides. Acidity, temperature, concentration and type of tanning agents, rotation of the drum and agitation are all variables that determine the quality of the tannage. Toward the end of this retannage, aluminum salts are added so as to reduce acidity of the leather, and to enhance archival characteristics of the Chieftain leather. This additional process serves to create a Ph buffer against possible the corrosive effects of air pollution to the leather over the decades to come.

Here’s a view inside the drum. Once the retannage is completed, the tanning liquor is drained from the drum, and an aniline dye is introduced. Being transparent, the aniline dye will enhance the natural grain of the leather (rather than disguise the grain which an opaque pigment would do). We specified a rich, green colour for LABYRINTH SUBLIME, inspired by the mosses, lichens, and foliage of the rainforest of The Inside Passage.

Roger removes the dyed goat hides from the revolving drum and lays them, one atop another, on a cylinder to avoid creasing. This is called “horsing up.” Now that the hides have been tanned, they are left “horsed up” for several days while hydrogen bonds strengthen and stabilize between the hide and the vegetable tannins.

A few days later the leather will be wrung between rollers to remove excess water and then hung to dry on toggle frames in an oven.

All hides naturally vary in thickness from one part of the hide to another. The spine and neck, for example, are relatively thick while the belly is relatively thin. When the leather is thoroughly dry, the thickness of the leather is levelled on the Dry Shaving Machine. This machine evens out the calliper, accurate to within ±0.05mm, by fluffing the flesh side on an emery wheel and leaving the grain side untouched. Here Raymond Ferguson feeds leather into the Dry Shaver.

Roger holds a handful of the shavings. This is the sort of material that other firms use to make composite leather, which somewhat misleadingly is marketed as “genuine leather.”

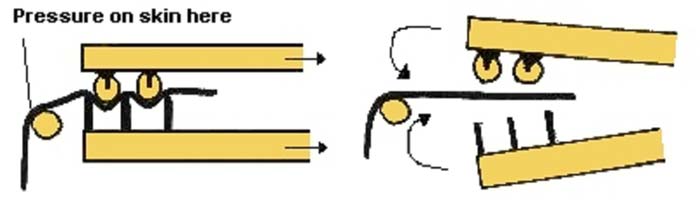

Further processing is required as the leather is now flat and quite stiff. In North America, prior to the adoption of white-man’s clothing, the teeth of native women would become quite worn from years of chewing deer and moose leather, their method of softening leather for clothing and moccasins. Fortunately at Hewits, all the women still have their teeth as there is an ancient-looking Staking Machine that does a similar process. It’s a rather violent jaw-like device that grabs, pulls, stretches, and flexes the leather, while the operator performs a sort of tug-of-war, retracting the leather out of the the machine, which then grabs it anew.

The photo above doesn’t show the whole picture, which the illustration below does. A movie would be best. We found this to be a rather scary, crocodile-like machine.

In the finishing department, Mary McDougall feeds LABYRINTH SUBLIME’s Chieftain goat leather into the Spraying Machine where it receives an aniline/casein finish. The spray of additional aniline dye serves to bring the surface colour up to the exact specified shade. The initial basic dye, applied earlier in the revolving drum, has soaked through and coloured the entire hide inside and out. Thus the spray of additional dye on the surface of the top grain creates a very interesting two-toned effect. The casein, a protein that comes from milk, serves as the binder that adheres these pigments to the leather surface while also creating a uniform surface that will polish beautifully. Chieftain leather will receive between two and eight light coats of colour and casein in order to achieve the desired effect.

After the spraying is complete, the leather is hung to dry.

In the photo below Roger demonstrates with a small piece of Chieftain how this natural grained leather is burnished. He uses the Glazing Machine, which swiftly and repetitively drags a fixed glass cylinder across the flat tops of the leather’s natural grain thereby polishing these tops to a lovely shine further enhancing the two-toned effect of the dyes.

The final step is one that Roger Barlee personally undertakes, and that is the cutting of our pieces. Each of our tomes uses two large pieces of leather on the covers plus the two additional pieces for the leather joints (inside the front and back covers joining the cover to the end-leaves). Each presentation box uses two pieces of leather: the spine piece and the frontice piece. These six pieces of leather required for each volume are personally cut from the leather hides by Roger. He looks at each individual hide under multiple light conditions to spot any blemishes, which he marks with a pen. He then cuts our pieces making best use of the leather.

We expect that you may have discerned that the production of this high-quality leather is more of a passion than a business. No doubt, Chieftain Grade I is a very expensive leather to produce. We have selected this specific book leather for LABYRINTH SUBLIME and for ANTARCTICA because it is simply the best available anywhere in the world today.

We hope the insights above have helped you to appreciate the morocco that so elegantly binds ANTARCTICA and LABYRINTH SUBLIME. We also hope that the tradition of producing very fine book leathers will continue at Hewits through to future generations. Fortuitously, Roger Barlee’s youngest child shows interest.

With very best wishes,

Rosemarie and Pat